I do love the Octane Standalone renderer.

I’m probably unique within the Archviz industry in opting for the Octane Standalone renderer as much as I do. The image above, taken from OTOY’s demo scenes, is the first one I rendered with it after downloading the demo.

Cute isn’t it.

More importantly, look at the depth of field!

Rendering within seconds on my (very loud and very hot) GTX 590, and depth of field for free?! This was unheard of back then.

Over my working life, I’d slogged it out with 3ds Max’s Scanline renderer (‘renders everything you ever saw’, not sure it did), Mental Ray and then of course VRay. VRay is, of course, great rendering software, and it had a dramatic effect on the London studios when it arrived, as had Mental Ray (in truth, we only used the ambient occlusion shader and carried on faking things in Scanline.. Only the very bravest battled it out with Photon Tracing and Final Gather..).

VRay removed all that. Incidentally this is before Corona, which is another great renderer and probably now the most popular, for good reason and it does gorgeous reflections.

Back to Octane. The other renderers were at that time ‘coffee cup’ renderers; set a test render going, go and make a coffee, come back in 10 minutes. Press stop, tweak a light, or material shader, press render again, go and make another coffee.. Not the most conducive workflow.

Not so with Octane. Octane is a true ‘path tracing’ WYSIWYG renderer, and it will start producing a very grainy image instantaneously, allowing a valuable preview within a few seconds. For sure, this is pretty commonplace now, but it wasn’t back then in 2012.

The image below is rendered with just a few samples, and it’s more than enough to see where things are heading.

So. Realtime feedback, what’s not to like?

But why the Standalone version? Why not the in-built API for 3ds Max, that sits within the 3ds Max environment, or other modelling software of choice?

Two reasons. Back then it wasn’t free (albeit they now come with a subscription), but the more important thing for me, is that Octane Standalone is a renderer, nothing else. No modelling (not then anyhow), just lights (an HDRI environment or a daylight system), materials, cameras and action! 3ds Max, Blender or whichever for modelling, Octane for rendering.

You are often dipping back into 3ds Max, fixing and adding things to the model, re-exporting OBJ files, but there is something nice about being able to ‘leave the polygons behind’, and concentrate on composition, lighting and materials.

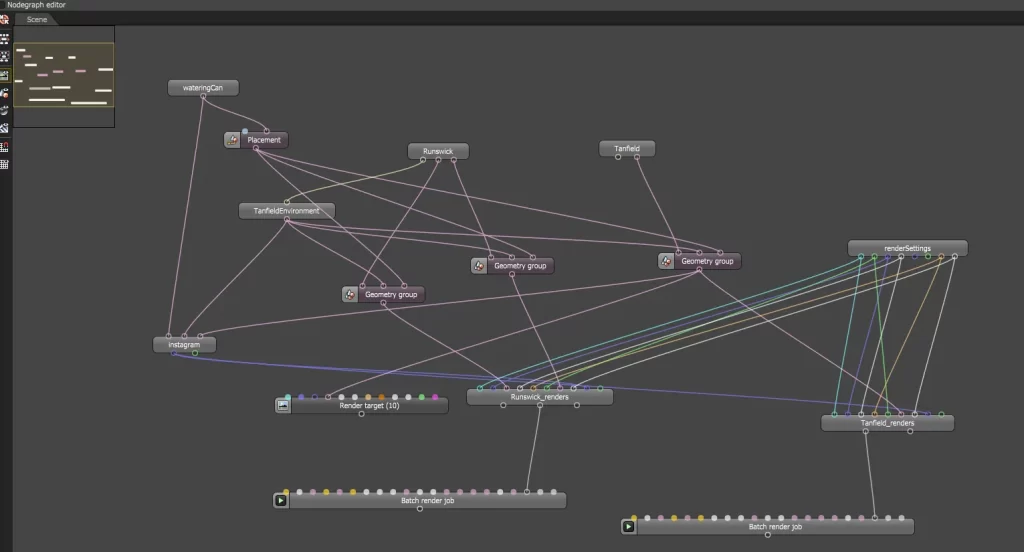

There’s something quite nice about the stripped down, node based interface too, almost like ‘Nuke for rendering’.

It doesn’t stay unclutted for long though, and the image below is showing a relatively organised project..

Things are better now with the use of ‘Node Graph’ objects, allowing you to group things together neatly.

Quirks? There are some, there wasn’t an ‘Undo’ for ages! That was tough going.

Fireflies (bright pixels appearing in the render seemingly from nowhere) are tamed using the ‘Hot Pixel Remover’ in the camera imager node, slide this to the left until they go. Some artists are uncomfortable with this, as it’s inbuilt image post-processing, but it works.

![]()

Pixel filter size, it’s softer than other renders but then as Archviz artists we’re historically used to sharper anti-aliasing filters, and of course there is the constant depth of field. This actually works I find, when working on photo-montaged images. You could always dial in a ‘non-real world’ camera aperture size, if you wanted that ‘super sharp CG’ look back. Some clients have remarked that they prefer the softer image look, so I’m assuming it’s this they are referring to.

As an Archviz artist, I find OTOY’s connections to the Motion Picture industry and the burgeoning Holographic industry interesting. Features pertinent to rendering for motion pictures are incorporated and updated frequently into Octane, and thus filter down into our more gentle world of property illustration.

I suspect most of us working in property illustration aren’t fully up to the ACES colour workflow (the ‘Academy Colour Encoding System’ no less!), and indeed the use of ‘Deep Images’ and ‘Cryptomattes’ for compositing purposes. We’re not ordinarily producing a series of channels and masks for VFX compositing (there are tons of ‘Arbritary Output Variable’ images that can be saved out from Octane).

That said, the ‘Info Channels’ rendering kernel is good for ‘quick and dirty’ ID passes, ZDepth and Ambient Occlusion. I find it quicker to render these out all separately (each with a lot less samples than the beauty render).

The cloud rendering, based on blockchain technology is amazing! It’s low cost and works very well. Best to have the current version of Octane though, don’t make the mistake as I did, of uploading a large project based on an earlier version, and then watch each frame being rejected, one by one.

Building a decentralised GPU cloud rendering network is a very ‘OTOY thing’ to do. There is an active user forum, which guides Octane’s development in equal measure to new and evolving techniques in rendering. OTOY’s founder Jules Urbach’s ‘The Future of Rendering’ talks at the NVIDIA GPU Technology Conferences are an interesting watch too.

I should point out that I’ve not been endorsed by OTOY in writing any of the above, these are my own thoughts as an end user. Over the next few months I’ll provide some further insights, tips and tricks with Octane.

Is it weird to fall in love with software? Probably.

I’m just a big fan of the Octane Standalone renderer.